A decade after Paris, global climate efforts continue to fail not just in execution, but in design. Here’s how to build an equitable path forward that addresses Africa’s unique position.

Ten years after world leaders gathered in Paris to forge a historic climate agreement, the State of Climate Action 2025 report delivers sobering news: of 45 key indicators for limiting warming to 1.5°C, not one is on track to achieve its 2030 target. Public finance for fossil fuels has increased by an average of $75 billion per year since 2014, reaching more than $1.5 trillion in 2023, whilst deforestation, which had declined earlier in the decade, is once again rising.

Yet the deeper failure is conceptual. The global climate conversation treats all nations as equally responsible for emissions and equally capable of addressing them. This assumption obscures a fundamental reality: climate change exhibits extreme asymmetry between those who caused it and those suffering its consequences. Until business leaders, policymakers, and financial institutions recognise and operationalise this asymmetry, climate strategies will remain both ineffective and unjust.

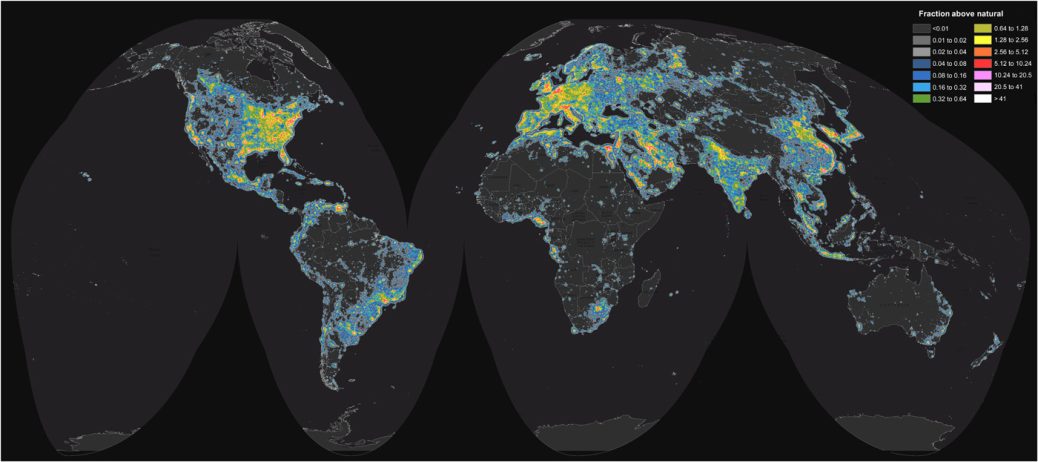

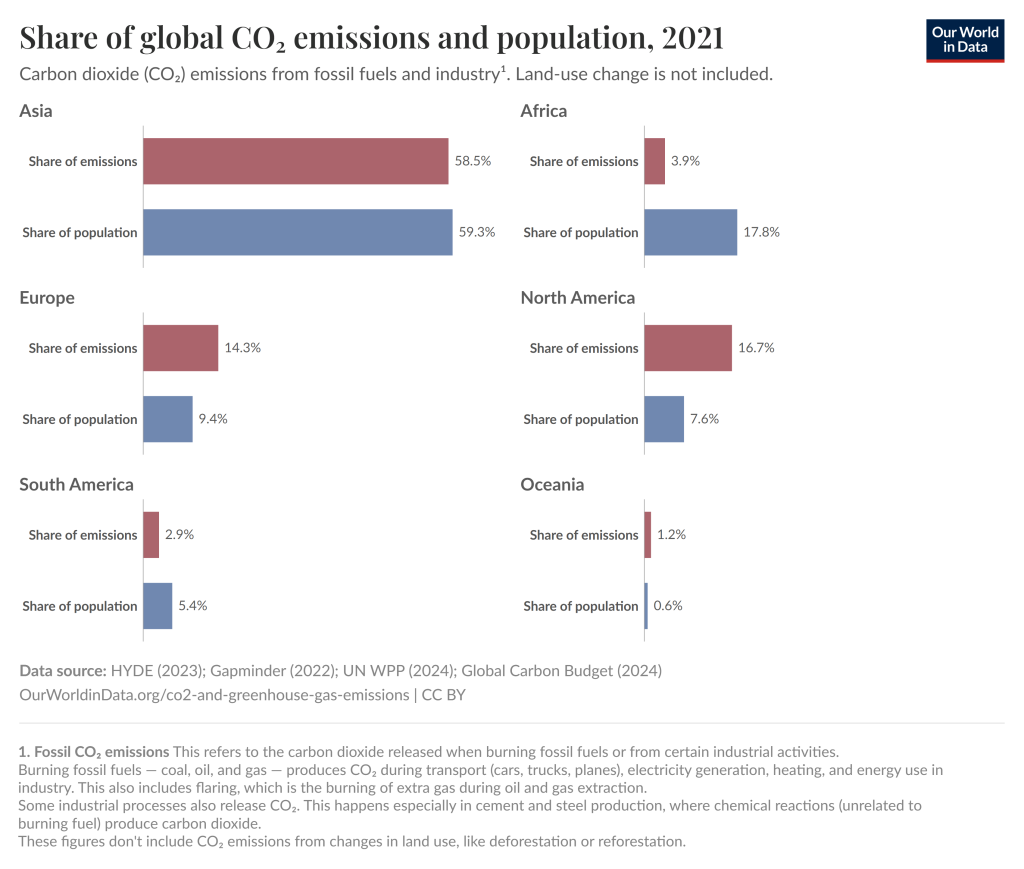

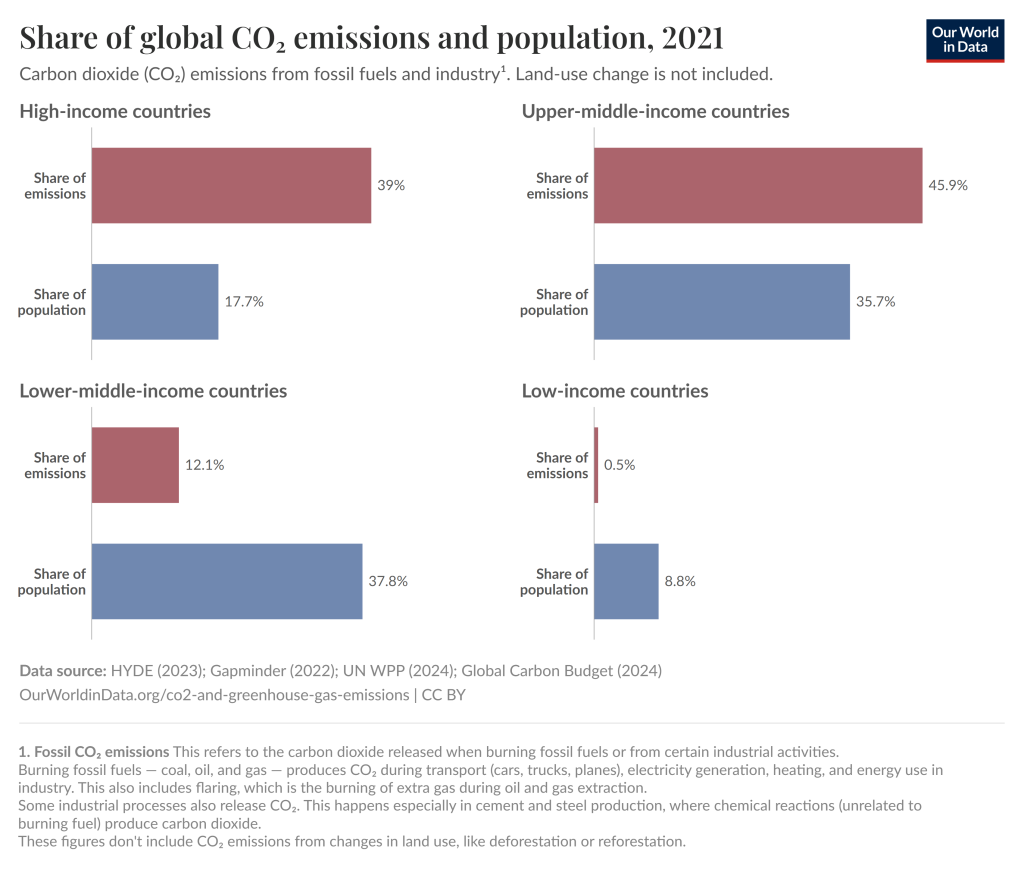

Consider Africa’s position. With a mean of 1,373 million tonnes of CO2 per year, total African fossil CO2 emissions over 2010 to 2018 represent only 4% of global fossil emissions. Yet Africa faces severe impacts of climate change despite contributing less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with an average of 1 tonne of CO2 emitted annually by each individual compared to 10.3 tonnes in North America. Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) has contributed just 1.9% of cumulative emissions since 1850, with the other 48 countries contributing just 0.6% whilst housing 14% of the global population.

This disparity matters not merely for ethical reasons, but because ignoring it produces unworkable strategies. When climate action plans call for ‘the world’ to retire coal plants, reduce consumption, or shift to electric vehicles, they implicitly demand equal sacrifice from profoundly unequal actors. To put that in perspective, an average American or Australian emits as much CO2 in a month as an individual in Africa does in a year. More than 600 million Africans lack electricity access entirely. They have no coal infrastructure to retire, no private vehicles to electrify, and consumption levels already orders of magnitude below what’s required to meet basic needs.

The strategic question is not whether climate action is urgent (it manifestly is) but how to design interventions that account for differential responsibility, capability, and vulnerability. This requires moving beyond one-size-fits-all targets to a stakeholder-segmented approach with distinct pathways for different actor categories.

Segmenting the climate challenge

Effective climate strategy must recognise at least four distinct stakeholder groups, each with different roles, capacities, and obligations:

Historical Emitters (United States, European Union, Japan): These economies industrialised over two centuries using fossil fuels and are responsible for the majority of cumulative atmospheric CO2. They possess advanced technological capabilities, deep capital markets, and GDP per capita exceeding $40,000. Their strategic imperative is rapid, near-total decarbonisation whilst financing climate action elsewhere.

Since 1850, the United States alone has contributed 25% of global cumulative emissions; Europe adds another 22%. These regions must lead on mitigation not as charity but as accountability for historical externalities imposed on others. Their coal plants must close, their transport systems electrify, and their consumption patterns transform, not because everyone must make equal sacrifices, but because they bear disproportionate responsibility.

Emerging Industrial Powers (China, India, Brazil): These nations are currently industrialising and account for growing shares of annual emissions, yet their per capita emissions and historical contributions remain below wealthy nations. China’s per capita emissions now approach Europe’s, but its cumulative responsibility is far lower. India’s per capita emissions are one-third of the global average despite being the world’s most populous nation.

These economies face a dual imperative: continuing poverty reduction and infrastructure development whilst pioneering clean development pathways. This requires massive technology transfer, concessional financing, and the ability to balance near-term development needs against long-term sustainability. The strategic challenge is avoiding the high-carbon development trajectory that enriched the West whilst building prosperity through renewable energy, efficient systems, and leapfrog technologies.

Vulnerable Low-Emitters (Sub-Saharan Africa, Small Island Developing States, Least Developed Countries): These nations contribute negligibly to emissions but face existential climate threats. Their primary need is not mitigation but adaptation and development. The African Development Bank’s African Economic Outlook estimates Africa needs about US$2.7 trillion by 2030 to respond adequately to climate change.

For these stakeholders, climate strategy must centre on building adaptive capacity, delivering energy access through renewable infrastructure, and securing compensation for loss and damage from climate impacts they did not cause. Demanding emissions reductions from people consuming 50 to 100 kWh of electricity annually (versus 10,000 or more kWh in wealthy nations) is not merely inequitable but absurd.

Fossil Fuel Incumbents (Major oil companies, coal producers, petrostates): These actors possess tremendous political and economic power built on extractive business models incompatible with climate stability. Some are pivoting towards renewables; many are doubling down on expansion. Their strategic challenge is managed decline and just transition: redeploying capital, retraining workforces, and restructuring economies dependent on hydrocarbon revenues.

A Differentiated Strategy Framework

Acknowledging these distinct stakeholder positions enables more sophisticated strategy than universal targets permit. Here’s what differentiated climate action requires:

1. Reframe Climate Finance as Restitution, Not Aid

At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the UNFCCC in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries committed to a collective goal of mobilising USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries. Developed countries provided and mobilised USD 115.9 billion in climate finance for developing countries in 2022, exceeding the annual 100 billion goal for the first time and reaching a level that had not been expected before 2025. However, this achievement came two years late and represents a fraction of actual need.

Based on data from 51 out of 53 African countries that submitted Nationally Determined Contributions, it will cost around USD 2.8 trillion between 2020 and 2030 to implement Africa’s NDCs. However, only a fraction of this funding is currently available. Despite pledges at COP26 in Glasgow to double adaptation finance for developing countries, Africa receives only 3 to 4% of global climate finance.

Current climate finance architecture treats these flows as development assistance rather than compensation for historical externalities. This framing error has profound consequences: it makes finance appear discretionary rather than obligatory, it allows wealthy nations to claim credit for inadequate contributions, and it fails to mobilise capital at the required scale.

Business leaders and financial institutions must recognise climate finance as addressing a massive unpaid debt. Every tonne of CO2 emitted by wealthy nations over two centuries imposes adaptation costs on vulnerable populations today. From this perspective, climate finance is not generosity but partial restitution for damages caused.

This reframing has practical implications. It shifts the burden of proof: rather than African nations justifying why they deserve funding, wealthy nations must justify why they aren’t providing adequate compensation. It changes financing structures: compensation deserves grants, not loans that add to debt burdens. And it clarifies accountability: wealthy nations failing to provide adequate climate finance are defaulting on obligations, not merely missing voluntary targets.

2. Implement Asymmetric Carbon Pricing

Carbon pricing is economically efficient but politically toxic when designed as universal levies. A justice-oriented approach would implement strongly progressive carbon pricing that exempts low emitters whilst imposing escalating costs on high emitters.

Consider a tiered system: nations or individuals emitting below 2 tonnes CO2 annually (the sustainable per capita target) pay nothing. Those emitting 2 to 5 tonnes face modest carbon prices. Emissions above 10 tonnes incur sharply escalating prices, with revenues flowing to adaptation funds for vulnerable nations.

This addresses the legitimate concern that carbon pricing burdens the poor whilst creating powerful incentives for high emitters. An American household emitting 40 tonnes annually faces far higher carbon costs than an Indian household emitting 2 tonnes, proportional to their contribution to the problem.

Several multinational corporations are already implementing internal carbon pricing mechanisms. Extending this logic internationally through border adjustment mechanisms and trade agreements could create an effective progressive system without requiring universal treaties.

3. Prioritise Technology Transfer and Capacity Building

Africa possesses some of the world’s greatest renewable energy potential: the Sahara receives more solar radiation than anywhere on Earth, the Great Rift Valley offers vast geothermal resources, and coastal regions have exceptional wind potential. Yet the continent has installed just 5 gigawatts of solar capacity compared to 300 gigawatts in China and 100 gigawatts in the United States.

The barrier is not resource availability but access to technology, financing, and expertise. Wealthy nations and corporations hoarding green technologies through restrictive intellectual property regimes perpetuate climate injustice whilst slowing global decarbonisation.

A justice framework would treat clean technology as global public goods, making patents freely available to developing nations or licensing them at nominal cost. It would fund African institutions to build domestic renewable manufacturing capacity rather than maintaining dependence on imported systems. And it would prioritise workforce development so African engineers, not external consultants, design and maintain clean infrastructure.

Some progress is emerging: Morocco’s Noor Ouarzazate complex demonstrates large-scale concentrated solar power, Kenya generates 90% of electricity from renewables, and Ethiopia is building Africa’s largest wind farm. But these remain exceptions. Scaling such successes requires deliberate technology transfer policies that currently don’t exist.

4. Restructure International Development Finance

The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and regional development banks continue financing fossil fuel projects whilst climate adaptation funding remains inadequate and difficult to access. Further analysis of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) also indicates that the adaptation finance needs for the continent over the period 2020 to 30 are close to $580 billion, yet an annual average of $29.5 billion in climate finance was committed to Africa in the years 2019 and 2020, of which about $11.4 billion, or 39%, was for adaptation investments.

African nations report that accessing climate finance requires navigating complex bureaucracies, meeting stringent requirements often misaligned with local contexts, and accepting loan terms that worsen debt burdens.

This architecture must be fundamentally restructured. Climate adaptation finance should be grant-based, not loan-based, recognising that vulnerable nations are addressing problems they didn’t create. Application processes must be simplified and localised, empowering African institutions to design and implement projects rather than requiring external consultants. And financing must be outcome-focused: building resilience, expanding clean energy access, and supporting economic development, not merely reducing emissions.

According to the Global Center on Adaptation, only seven African countries have all the key strategic and planning elements to absorb larger adaptation finance. There are important opportunities to learn and replicate lessons from these countries across the region.

5. Build African Climate Leadership

Rather than treating Africa as passive victim requiring rescue, climate strategy should recognise the continent’s potential leadership role. Africa can pioneer clean development pathways, demonstrate how to build prosperity without fossil fuels, and lead global conversations about justice and equity.

This requires investing in African climate institutions, empowering African negotiators in international forums, and supporting African innovation in renewable technology, climate-smart agriculture, and adaptation strategies. African negotiators are seeking more finance, including a binding commitment from developed economies greater than $100 billion by 2020. They are also warning that new public finance should be used to fill the climate financing gap and that existing official development assistance should not be simply relabelled as climate finance.

African nations are already demonstrating leadership: Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy strategy, Rwanda’s ambitious emissions reduction targets despite negligible historical responsibility, and the African Common Position bringing unified continental voice to climate negotiations. Amplifying these efforts serves global interests: Africa’s successful clean development would prove pathways for other regions whilst avoiding massive emissions if Africa followed fossil fuel trajectories.

Implementation: What Leaders Must Do Now

For CEOs, investors, and policymakers committed to effective climate action, the justice framework implies specific immediate actions:

Multinational Corporations: Audit your supply chains for emissions asymmetry—ensure you’re not offshoring pollution to vulnerable nations. Implement internal carbon pricing with revenues directed to climate adaptation in countries where you operate. Make clean technology patents freely available to least developed countries. Invest in building local renewable manufacturing capacity in Africa and other vulnerable regions.

Financial Institutions: Stop financing fossil fuel expansion in any form. Restructure climate finance portfolios to dramatically increase grant-based adaptation funding for vulnerable nations. Develop innovative financial instruments that mobilise private capital for African renewable energy at scale. Measure success not just by emissions reduced but by adaptive capacity built and energy access expanded in vulnerable regions.

Government Leaders in Wealthy Nations: Meet and exceed climate finance commitments; the $100 billion target is a floor, not a ceiling. Support technology transfer agreements that treat clean energy as global public goods. Implement progressive carbon border adjustments that exempt low emitters whilst imposing costs on carbon-intensive imports. Use development assistance to build African renewable energy and climate adaptation capacity.

Government Leaders in Vulnerable Nations: Build unified negotiating positions demanding justice-oriented climate agreements. Develop ambitious clean development strategies that demonstrate leadership rather than waiting for external solutions. Invest in domestic renewable energy capacity and technical expertise. Hold wealthy nations accountable for unfulfilled commitments whilst showcasing your own climate action.

Investors: Recognise that climate justice is not separate from climate action but essential to it. Unjust strategies will fail politically and practically. Direct capital towards African renewable energy, which offers both attractive returns and enormous social impact. Support climate adaptation infrastructure as a new asset class. Divest from fossil fuels entirely; the transition is inevitable, and late movers will suffer.

Why Justice Matters Strategically

Some may view this justice framework as idealistic or politically naive. The opposite is true: it’s strategically essential.

Climate change is a global collective action problem requiring cooperation across all nations. Cooperation depends on perceived fairness. Asking African nations to constrain development whilst wealthy nations maintain high consumption is both unjust and politically unsustainable. African negotiators will rightly refuse agreements that perpetuate historical inequities.

Moreover, the transition to clean energy creates enormous economic opportunities: trillions in new infrastructure investment, millions of jobs, new industries and markets. Whether these opportunities enrich incumbent powers or enable catch-up growth for developing nations depends on intentional policy choices made now.

Finally, climate impacts don’t respect borders. Africa’s instability from climate disruption (failed harvests, water scarcity, forced migration, conflict) will create global security, economic, and humanitarian challenges. Investing in African climate resilience is not charity but pragmatic self-interest.

Conclusion: Ten Years Lost, Time Remaining Precious

A decade after Paris, we face uncomfortable truths. The world must phase out coal more than ten times faster—equivalent to retiring nearly 360 average-sized coal-fired power plants each year and halting all projects in the pipeline. Permanent forest loss dropped from a record high of 10.7 million hectares per year in 2017 to 7.8 million hectares per year in 2021, but has since ticked upward to reach 8.1 million hectares per year in 2024, roughly equivalent to losing nearly 22 football fields of forest every minute.

But the deeper failure is treating this as a universal challenge requiring uniform sacrifice. Climate change is not an undifferentiated global problem; it’s the accumulation of two centuries of asymmetric industrialisation, where some nations grew wealthy by imposing costs on others. Addressing it effectively requires acknowledging this history and designing differentiated strategies based on responsibility, capability, and vulnerability.

The Africa Progress Panel notes that it would take the average Ethiopian 240 years to register the same carbon footprint as the average American. Africa’s position crystallises what’s at stake. The continent that contributed least to climate change suffers most from its impacts whilst possessing the least capacity to adapt. Yet Africa also represents humanity’s best hope for demonstrating that prosperity without fossil fuels is possible, if the rest of the world provides the support that justice demands and strategy requires.

The path forward is clear: radical emissions reductions by historical emitters, massive climate finance flowing to vulnerable nations as compensation not charity, technology transfer treating clean energy as global public goods, and African leadership in designing equitable climate solutions.

We’ve wasted a decade treating climate action as a technical challenge of emissions reduction. The next decade must recognise it as fundamentally a question of justice. Not because justice is a nice-to-have addition, but because climate action without justice will fail politically, practically, and morally.

The systems are indeed flashing red, as the climate report warns. But they’re flashing red unequally. It’s time our strategies reflected that reality.

Sources and Methodology

This article draws on peer-reviewed research, institutional reports, and official climate finance data from the following sources: Mostefaoui et al. (2024), “Greenhouse gas emissions and their trends over the last 3 decades across Africa,” Earth System Science Data; Al Jazeera analysis of African emissions data (2023); Energy for Growth Hub analysis of Sub-Saharan African emissions (2025); African Development Bank Focus on Africa report (2024); Brookings Institution climate adaptation finance analysis (2023); Climate Policy Initiative’s “Climate Finance Needs of African Countries” (2025) and “Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa” (2022); OECD reports on the USD 100 billion climate finance goal; State of Climate Action 2025 report by Systems Change Lab; and Brookings Institution reports on African climate finance and Paris Agreement negotiations.

By Ethical Business Analysis Desk