Africa’s halting progress on disease preparedness exposes the gap between rhetoric and resources

By Our Staff Writer

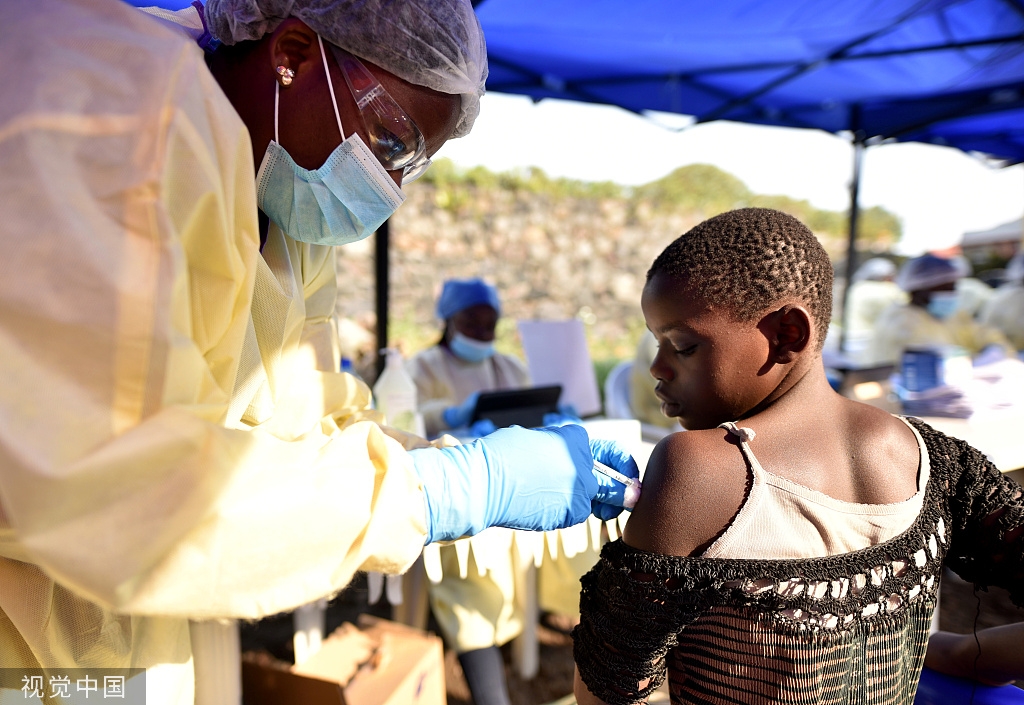

In February 2025, Africa was grappling with 54 active disease outbreaks and 82 ongoing public health events, according to data from regional health surveillance systems. For a continent that faces more than 100 disease outbreaks annually, the statistics have become grimly routine. Yet behind these numbers lies a fundamental question: whether Africa’s post-COVID investments in pandemic preparedness will translate into genuine resilience or prove another cycle of crisis response followed by institutional amnesia.

Between 2022 and 2024, disease outbreaks on the continent surged by 41 per cent, from 166 events in 2023 to 213 in 2024, according to Jean Kaseya, director-general of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. By year’s end, cholera had killed 3,747 people across the continent, whilst mpox claimed 1,321 lives and measles another 3,220. In January 2025, Kaseya warned that the continent remained in crisis mode, identifying cholera, measles, dengue, mpox and diphtheria as the five high-burden diseases.

“We see that the number of disease outbreaks in 2024 was more than in 2023,” Kaseya said then. “In 2024, we had 213 events, while in 2023, we had 166. We hope that this year will be different from the last year.”

He framed the challenge more bluntly. “In Africa, from 2022 to 2024, we saw an increase of 40 per cent in terms of infectious disease outbreaks,” he said. “We moved from 152 to more than 242 outbreaks in just two years. This is huge.”

Kenya epitomises both Africa’s ambitions and its contradictions in pandemic preparedness. The country has positioned itself as a regional hub, hosting the World Health Organisation’s emergency response centre for Africa and endorsing multiple regional initiatives. In August 2025, Mary Muthoni, principal secretary for public health and professional standards, announced Kenya’s support for the Pandemic Preparedness and Response Initiative, a regional programme covering the Horn of Africa through the Intergovernmental Authority on Development.

“Our region faces common risks that do not respect borders,” Muthoni told delegates at the initiative’s launch in Uganda. “Only through united action can we build a resilient system capable of withstanding future crises.”

Yet Kenya’s economic constraints cast a long shadow over such commitments. The country’s real GDP grew by 4.7 per cent in 2024, down from 5.7 per cent the previous year, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. With a fiscal deficit of 4.3 per cent of GDP and debt servicing consuming an expanding share of government revenue, the space for health investments remains squeezed. The finance ministry’s 2024-2025 budget allocated no dedicated pandemic preparedness fund, a pattern replicated across most of East Africa.

The financing gap has become continental. Official development assistance for health across Africa plummeted by 70 per cent between 2021 and 2025, according to Africa CDC’s strategic health financing analysis published in April 2025. “From 2021 to 2025, we are moving from 81 billion dollars annual to almost 25 billion dollars of foreign assistance in the health area in Africa,” Kaseya said. “It’s a huge decrease, a 70 per cent decrease. And when you have this kind of huge decrease, you cannot wake up one day and say, ‘I can cover that cost.'”

This collapse in external funding arrives precisely as Africa’s disease burden intensifies. The continent carries 25 per cent of the world’s disease burden whilst producing only one to two per cent of global health research publications. “We have an environment where, first, there’s an increase in outbreaks,” Kaseya said. “Second, there’s climate change. Third, there’s insecurity. Fourth, there’s a lack of resources. We are building the foundation for another pandemic.”

International mechanisms have attempted to fill the void, with mixed results. The Pandemic Fund, established in September 2022 and hosted by the World Bank, approved USD 234 million for African projects in its third call for proposals in November 2025, roughly 47 per cent of the fund’s USD 500 million total allocation. These grants have mobilised an additional USD 6 billion in co-financing, representing a 1:7 leverage ratio, according to fund co-chairs Chatib Basri and Sabin Nsanzimana.

South Africa received USD 25 million to strengthen surveillance systems and laboratory capacity, catalysing USD 27 million in co-investment. Priya Basu, executive head of the Pandemic Fund, described the approach at the January 2025 launch in Pretoria. “South Africa’s new project is a timely and strategic investment in strengthening health security through a One Health approach,” Basu said. “By enhancing disease surveillance, laboratory systems, and the health workforce, the country is bolstering the foundation for long-term pandemic resilience.”

Eight southern African countries secured USD 36 million for climate-resilient health security, focusing on flood and drought-related disease threats. In May 2025, Kenya ratified the WHO pandemic treaty, which mandates pharmaceutical companies to contribute 20 per cent of vaccines and therapeutics production to a global distribution system based on public health need.

These investments target genuine vulnerabilities. The February 2025 Africa Pandemic Sciences Collaborative, a partnership between the Science for Africa Foundation, Oxford University’s Pandemic Sciences Institute and the Mastercard Foundation, highlighted critical workforce shortages. Africa contributes 17 per cent of the global population but faces chronic underinvestment in scientific capacity, particularly for early-career researchers.

The East African Community’s Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response Policy Framework, approved in May 2025, addresses coordination failures laid bare by COVID-19. Kamene Kimenye, acting director-general of Kenya’s National Public Health Institute, noted that health threats in one partner state rapidly spill across borders in a shared economic space of more than 300 million people.

“We are in an era of emerging and re-emerging public health threats,” Kimenye said at the May launch of Kenya’s National Public Health Institute. “Public health functions are best served when there is a single focal point.”

On the East African policy framework, Kimenye added, “This policy framework offers a comprehensive blueprint to strengthen resilience through cross-border coordination, digital innovation, sustainable financing and meaningful community engagement.”

Implementation, however, remains the test. Andrea Aguer Ariik Malueth, East African Community deputy secretary general, acknowledged that most partner states lack dedicated pandemic preparedness funds, relying instead on emergency reallocations during crises. The policy identifies critical gaps: fragmented coordination, insufficient financing, weak surveillance systems, health worker shortages and limited community engagement.

Africa’s strategic response has evolved through distinct national approaches. Research published in March 2025 categorised African states into three groups: policy-advanced countries such as Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda, which prioritise securitisation and border surveillance; scientifically advanced states including South Africa, Ghana and Nigeria, which emphasise research capacity; and fragile states like Somalia and Democratic Republic of Congo, where conflict diverts resources from health systems.

Kenya’s approach combines military-managed public health institutes with cross-border cooperation. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which established its Kenyan office in 1979, has supported training for more than 1,500 epidemiologists through the Field Epidemiology Laboratory Training Programme. These graduates respond to more than 80 per cent of outbreaks detected in the country, according to CDC data from December 2025.

At the May launch of Kenya’s National Public Health Institute, Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale framed the institution’s purpose. “National Public Health Institutes are so vital,” Duale said. “Around the world, NPHIs serve as centralised hubs that bring together surveillance, emergency response, health research, and policy coordination under one roof. It is within this context that I am proud to announce the official launch of the KNPHI.”

Yet domestic political constraints persist. A 2024 study examining Kenya’s post-COVID recovery found that 91.6 per cent of households received no government assistance during the pandemic. Only 10.2 per cent expressed satisfaction with the government’s COVID-19 response, whilst similar proportions doubted future crisis preparedness. One stakeholder interviewed for the study captured the financing challenge. “I think for COVID, and we don’t know how many other pandemics we are yet to get into, is how efficient we are in our Public Finance Management, especially in fund flows to getting the money to where it is needed in good time,” the respondent said. “We failed in terms of timely disbursements.”

The cost-benefit calculation for pandemic preparedness grows more compelling with each outbreak. Economic analysis suggests that every dollar invested in preparedness yields returns ranging from 1:7 in direct co-financing to broader economic protection through avoided lockdowns and health system collapse. Yet these future returns compete poorly against immediate fiscal pressures.

Africa CDC’s health financing strategy, launched in April 2025, proposes solidarity levies on airline tickets, alcohol and mobile services, alongside exploring how the continent’s USD 95 billion in annual diaspora remittances might support health priorities. The strategy urges governments to meet the 2001 Abuja Declaration commitment of allocating 15 per cent of national budgets to health, a target most countries continue to miss.

The strategy envisions phased implementation: updating national health financing plans in 30 countries by 2026, then scaling successful approaches to enable at least 20 countries to finance 50 per cent or more of health budgets domestically by 2030. Whether this timeline proves realistic depends on political will that has historically proved ephemeral.

Kaseya, addressing the November 2025 EU-Africa summit, framed the challenge facing the continent. “Achieving these ambitions demands more than technical solutions,” he said. “It requires political will, sustained investment and a unified approach that places Africa’s people at the centre.”

The WHO’s Preparedness and Resilience to Emerging Threats initiative, introduced to 21 African countries since April 2023, attempts to integrate respiratory pathogen pandemic preparedness into national health systems. The programme aligns with the global health emergency preparedness framework’s five priorities: collaborative surveillance, emergency coordination, access to countermeasures, clinical care and community protection.

Telstar Ghestin Ndong Mebaley, One Health focal point at Gabon’s National Public Health Laboratory, described the programme’s utility. “Using the PRET approach was instrumental in identifying key priorities and actionable recommendations to be put in place,” Mebaley said.

South Africa’s Science Minister Blade Nzimande, speaking at the January 2025 launch of the 100 Days Mission report in Cape Town, connected pandemic preparedness to Africa’s broader development agenda. “We are going to place pandemic preparedness as one of the key focus areas of South Africa’s G20 Presidency,” Nzimande said. “Therefore, we will be advocating for meaningful partnership in both the Research and Innovation Track and the Health Track as a way of strengthening science ecosystems for equitable innovation.”

Nzimande added context for Africa’s commitment. “The African continent is making progress towards the development of a sovereign African Research and Development, and Science Agenda,” he said. “The other reason for our commitment to pandemic preparedness arises from the tragic experience we had as the African continent during the same period, where we found ourselves hopelessly dependent on the vaccines from the Global North. This is why equitable international partnerships are critical to developing credible pandemic preparedness.”

Shingai Machingaidze, co-chair of the International Pandemic Preparedness Secretariat’s Science and Technology Expert Group and head of Africa Strategy at CEPI, reflected on continental progress. “The challenges highlighted in this report reaffirm the critical need for global collaboration and equitable approaches to pandemic preparedness,” Machingaidze said. “Africa’s response to emerging threats, like Rwanda’s rapid containment of the Marburg virus, demonstrates that with the right investments and partnerships, the 100 Days Mission is achievable.”

Yet such tools require sustained financing and political commitment to translate into operational capacity. The fundamental tension remains unresolved: pandemic preparedness demands sustained investment during quiet periods, precisely when competing priorities crowd budgets. Africa’s 242 disease outbreaks in 2024, well above the continent’s annual average, underscore both improved surveillance capacity and genuine escalation in disease burden.

“Just to give an example, in January, we had 82 outbreaks in Africa,” Kaseya said in March. “What’s that mean? Every day you have something coming.”

Climate change, biodiversity loss, migration and conflict create conditions for pathogen spillover, whilst limited laboratory capacity and antitoxin shortages complicate outbreak response. Kaseya, in December 2024, outlined the structural drivers. “The 2024 Global Preparedness Monitoring Board report highlights four critical pandemic risk drivers that urgently require action: agricultural practices, climate action, conflict and instability, and economic inequality impacting both the emergence and response capacity of public health emergencies,” he said.

Kenya’s multiple regional commitments, to IGAD, the East African Community, the WHO pandemic treaty and bilateral partnerships, create overlapping mandates that risk duplication. Success depends on harmonising these initiatives whilst maintaining flexibility to address local contexts.

The post-COVID settlement on pandemic preparedness appears fragile. As external financing contracts and domestic budgets face competing demands, the gap between preparedness aspirations and allocated resources widens. Africa’s improving surveillance systems detect more outbreaks, yet response capacity frequently lags detection.

“The risk is huge,” Kaseya said. “How do you want us to respond to all of these outbreaks if you don’t have vaccines, if you don’t have medicines, if you don’t have diagnostics, if you don’t have human resources, if you don’t have resilient health systems?”

The question is no longer whether the next pandemic will emerge, but whether Africa’s investments today will prove sufficient when it does.