Each month, thousands of tonnes of second-hand clothes arrive at Mombasa Port, tightly packed in plastic-wrapped bales. For many Kenyans, these garments represent affordability and livelihood. Yet behind this trade lies a deeper and more complex problem. Africa’s dependence on imported used clothing has created an environmental and economic imbalance that is now threatening local industries and ecosystems.

The scale of the problem

Data from the UN Comtrade Database shows that Kenya imported more than 185,000 tonnes of second-hand clothes in 2023, valued at around KES 22 billion (USD 140 million). The figure has tripled over the past decade as global consumption of fast fashion continues to grow. Across Africa, total imports exceed 900,000 tonnes a year, with Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania and Nigeria among the leading destinations.

The majority of these garments never make it to consumers. Research by the Changing Markets Foundation (2023) indicates that fewer than 30 per cent of imported clothes are resold or reused. The rest end up as waste, often in open dumps or along riverbanks. In Nairobi’s Dandora dumpsite, textiles now account for nearly 12 per cent of total waste, up from 4 per cent five years ago, according to the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

Much of this waste begins its journey in the Global North. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that 70 per cent of donated clothes in developed countries enter international resale markets, with a large share shipped to Africa. Traders in Nairobi’s Gikomba Market report that nearly a third of bales arriving at the port are unsellable because of damage or poor quality. These items are dumped immediately, creating an invisible waste stream that grows with each shipment.

The economics of dependency

The mitumba trade sustains an estimated two million livelihoods in Kenya, from port workers to street vendors. However, economic returns are uneven. A KIPPRA (2022) study found that only 7 per cent of profits generated along the value chain stay with local traders, while most accrue to overseas exporters and logistics intermediaries.

The influx of used clothes has undermined domestic textile manufacturing. Kenya’s cotton-to-apparel industry now operates at less than 15 per cent capacity, according to the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM). Similar trends are evident elsewhere on the continent. In Ghana, used garments account for about 60 per cent of apparel consumption, and in Nigeria, many textile mills have closed due to declining competitiveness.

Efforts to regulate the trade have been politically sensitive. In 2016, the East African Community (EAC) proposed a phased ban on second-hand clothing imports to revive local industries. The plan faced strong opposition from major exporting countries, including the United States. Most EAC members eventually reversed course, citing potential job losses. Only Rwanda implemented the ban, absorbing short-term trade penalties to protect its domestic textile sector.

The environmental cost

Across sub-Saharan Africa, around 5.8 million tonnes of textile waste are generated annually, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 2024). Much of it consists of polyester and other synthetic fibres that do not biodegrade. A study by Greenpeace Africa detected microplastic particles from textiles in the Nairobi River system, linking them to informal dumping and open burning.

The climate implications are equally serious. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that burning one tonne of synthetic textile waste releases about 3.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Informal waste pickers, many of them women and young people, face chronic exposure to hazardous smoke and chemical residues.

Still, the crisis is spurring innovation. Kenyan enterprises such as Africa Collect Textiles, EcoPost and Takataka Solutions are experimenting with models that convert waste fabric into new materials, including recycled boards, yarns and household products. These efforts demonstrate the potential for a circular textile economy that balances livelihood creation with environmental responsibility.

Reimagining Africa’s textile future

Experts suggest a threefold strategy for transformation: redesign, regulate and reinvest.

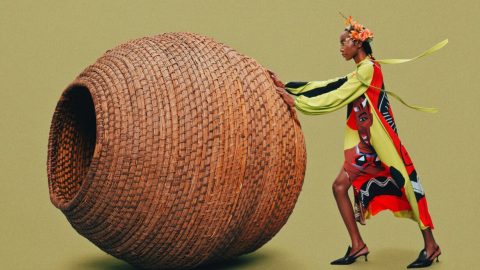

Redesign involves rethinking how clothing is produced and consumed. Kenyan fashion entrepreneurs such as Suave Kenya and Sevaria are building businesses around upcycling, turning discarded garments into premium fashion. Start-ups like Rethread Africa are developing biodegradable textiles using agricultural residues such as pineapple leaves and maize husks.

Regulation must ensure shared accountability. Kenya’s draft Sustainable Textile and Apparel Policy (2024) includes an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) scheme that requires importers and manufacturers to contribute to waste collection and recycling. This aligns with the Green Economy Strategy and Implementation Plan (GESIP), which envisions a zero-waste manufacturing system by 2030.

Reinvestment is equally important. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that a circular textile economy could unlock USD 8 billion in annual value by 2035, creating up to 2.5 million green jobs. Access to blended finance, carbon credits and climate funds could help scale recycling and data infrastructure across the region.

Why data matters

A major barrier to progress is the lack of accurate waste data. Few African cities track waste volumes by material type. This makes it difficult to design evidence-based policies or attract private investment in recycling. Initiatives such as the Africa Waste Data Portal, launched by UNEP and regional governments, aim to fill these gaps by mapping textile flows, landfill capacities and recycling rates.

Reliable data is more than a technical requirement; it is essential for governance and accountability. Without transparency, Africa risks remaining an endpoint in the global fashion economy rather than an active participant in building sustainable alternatives.

A closing reflection

Kenya and its neighbours stand at a turning point. Textile waste is both a symptom of global inequity and an opportunity for local innovation. By investing in data systems, circular business models and policy reforms, Africa can shift from being the world’s dumping ground to a hub of responsible textile production.

The numbers reveal the urgency. What happens next will determine whether Africa’s fashion future is built on waste or renewal.

By Philip Mwangangi